Otolaryngologist, head and neck surgeon Francis T. Hall discusses the evaluation of thyroid nodules, which primarily aims to determine the likelihood of malignancy. He then reviews the treatment of thyroid nodules and thyroid cancer, including recent advances in management

The first time using a ‘set piece’ to boost immunisation rates

The first time using a ‘set piece’ to boost immunisation rates

Rates of completed immunisations in New Zealand are falling. Specialist GP Jo Scott-Jones offers ways primary care can help address this concerning issue

This Practice article has been endorsed by the RNZCGP and has been approved for up to 0.25 credits for continuing professional development purposes (1 credit per learning hour). To claim your CPD credits, log in to your Te Whanake dashboard and record this activity under the appropriate learning category.

Nurses may also find that reading this article and reflecting on their learning can count as a professional development activity with the Nursing Council of New Zealand (up to 0.25 PD hours).

In a recent meeting with Ministry of Health clinical leaders, we were challenged with the ridiculously reductive concept that there is only one measure being used to determine whether primary care is successful in our health system – increasing childhood immunisation rates.

We do have to take this challenge from our funder seriously and trust that they do also value the comprehensive, continuous care for first-point-of-contact undifferentiated and chronic illness we provide in the community, but that they just don’t know how to properly measure what we do.

The complexity underpinning the falling rates of completed immunisations in New Zealand cannot be underestimated, and it certainly is not the sole responsibility of general practices to increase immunisation rates.

However, we all know that at the current national completed immunisation rate of 77.8 per cent at 24 months, and with a decline rate of 6.8 per cent at this age (tinyurl.com/imm-cov), our communities are vulnerable to outbreaks of preventable diseases, and yes, we need to play a part.

This is an area that lends itself to a set-piece conversation in your team. Everyone in the team – owners, managers, employees, clinicians and non-clinicians – can help plan and implement a set-piece response to various immunisation scenarios, just as a team might plan for and coordinate a scrum, corner kick or throw-in during a sports game.

You know people are going to need pre-call and recall for immunisations, they are going to come in seeking immunisations, and people who need immunisations are going to come for other reasons.

Take an hour to sit down together and discuss what each person currently says and does with each step in the immunisation process. I can guarantee there will be variations in approach in any clinical team. Decide as a group if these variations are important, and if they lead to significant confusion among patients.

One clinician might never mention immunisation during a consultation because they don’t want to antagonise patients; another might make it a priority for every consultation. How does this impact patients in your practice when they see different clinicians on different days?

One nurse might send a text message, another an email, and another only ever call patients on the pre-call/recall list. How does this impact patient engagement?

Does your practice reach out when a notification of a new birth is received? A simple congratulations card can be a lovely gesture that makes a connection with a family and reminds them that you care and are there for them.

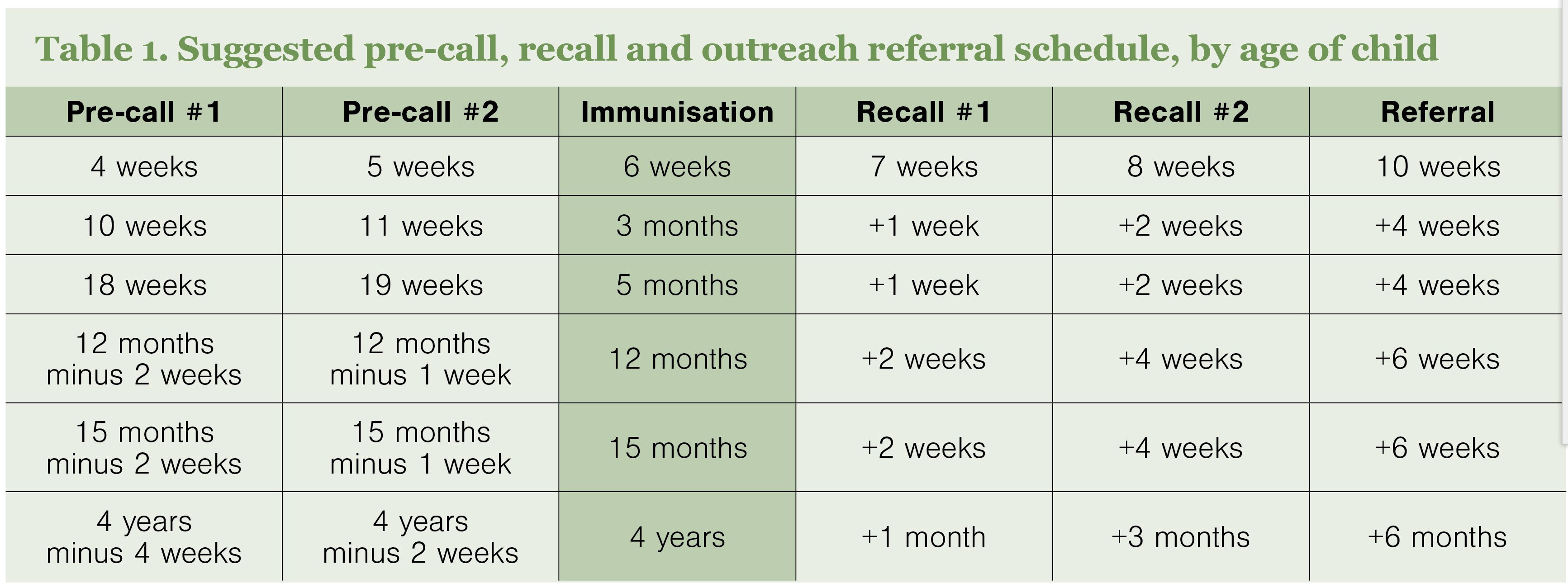

A systematic approach to pre-call and recall might include agreeing a time frame for each immunisation event, how communication will happen, what will be said by whom, and when referral to outreach immunisation services will happen (Table 1). You might agree that at each pre-call/recall, a text message and phone call will be made from a trusted clinician.

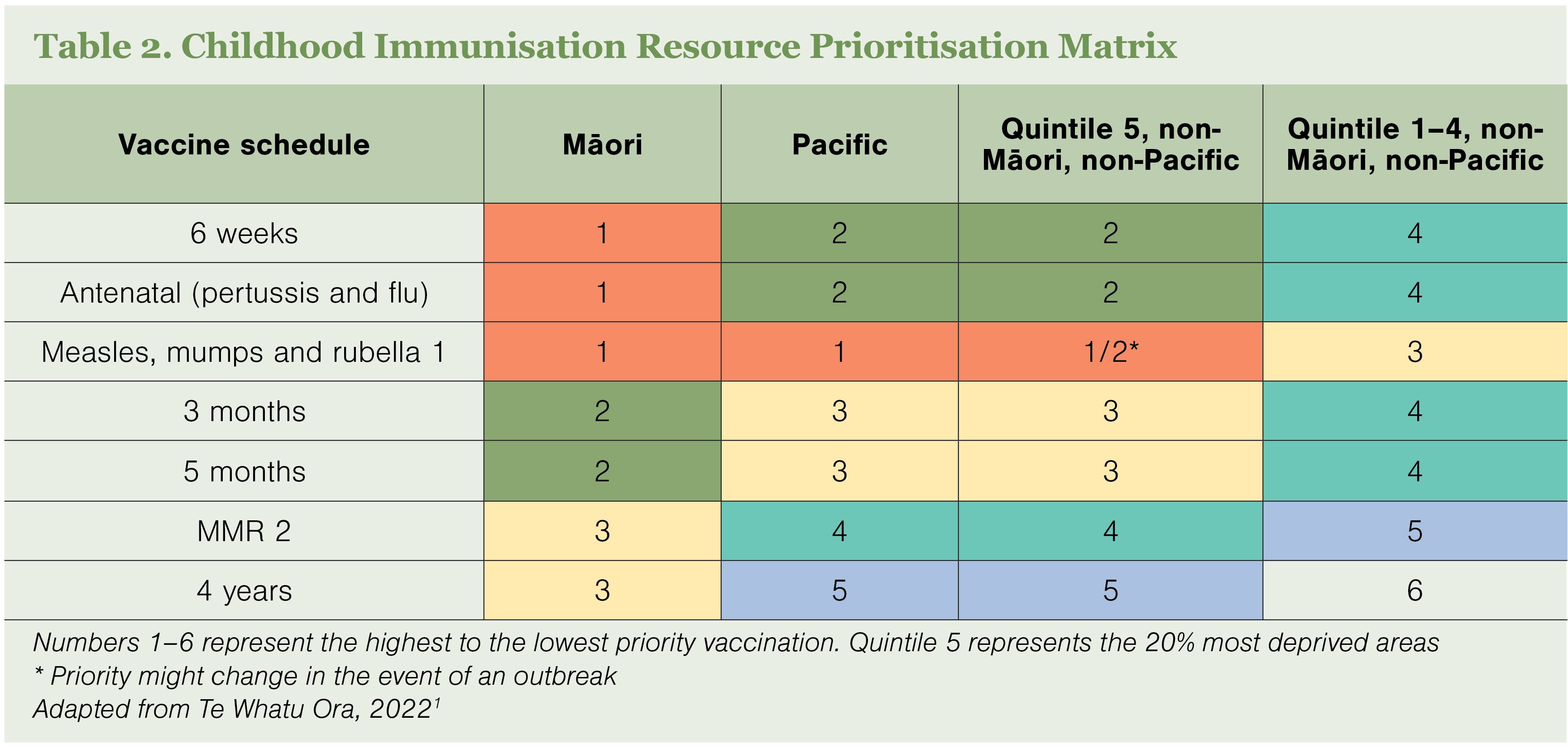

You might agree to use the Childhood Immunisation Resource Prioritisation Matrix from Te Whatu Ora (Table 2),1 to focus specific attention on highest priority families. You might also agree to involve culturally appropriate staff, or clinic partners in your community, to make connections and provide pre-call and recall reminders.

Teams may find value in considering the different attitudes and behaviours of people within the practice community

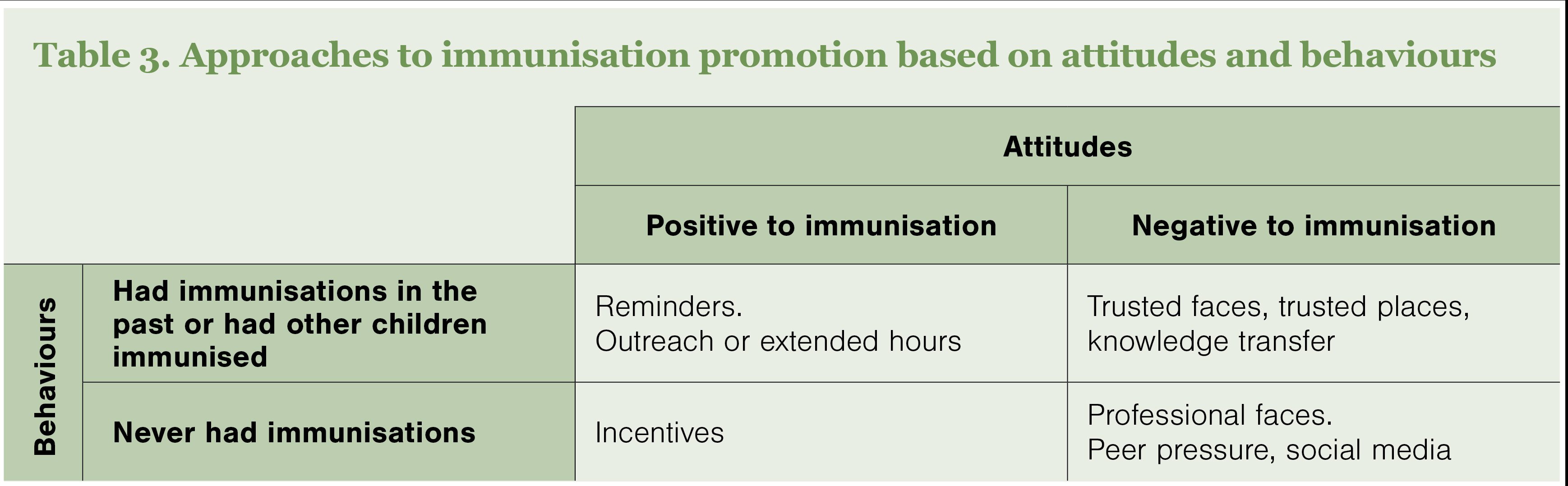

Beyond the routine pre-call and recall practises, teams may find value in considering the different attitudes and behaviours of people within the practice community.

In 1982, Sheth and Frazier described one model of social change that, when adapted to immunisation, provides a mix of four approaches to health promotion based on four attitude–behaviour patterns (Table 3):2

- Families who have had immunisations before and have positive attitudes to immunisations, but are now late or not having immunisations, may respond to being reminded of the benefits and being provided with easy access through outreach or extended hours.

- Families who have had immunisations before but have developed negative attitudes to immunisations due to anxieties may respond to rational arguments, especially from a trusted health professional (trusted faces, trusted places, knowledge transfer).

- Families who have never had immunisations but may have positive attitudes (perhaps they live in chaos or just busyness) may respond to inducements and rewards – some people will do anything for a frozen chicken (incentives).

- Families who have negative attitudes to immunisations and don’t have immunisations performed are the hardest group to change, but they may respond to sensitive yet direct warnings given face to face by expert health professionals (professional faces). Evidence also suggests the “determined decliners” may change their minds if their peer group changes its collective mind, sometimes as a result of a tragedy, admittedly, but friends and social media groups can play a big part in making this happen.

Your team might want to look at each of the whānau in your practice who are in the pre-call/recall phase and categorise them into an attitude–behaviour category, based on what you think their preferred main approaches might be.

If your population fit mostly into the determined decliner box, engaging with local paediatricians, immunisation coordinators and cultural partners may be a major focus. If your people are mostly positive about immunisation, outreach, extended hours and incentives could be more effective.

First, you save yourself. Immunisation is a complex problem, with many factors impacting uptake. Your team can only do their best. Don’t take it all on. Partner with others and ask for help from your PHO, cultural partners in the community and the public health service.

Jo Scott-Jones is medical director for Pinnacle Midlands Health Network, has a general practice in Ōpōtiki and works as a specialist GP across the Midlands region

You can use the Capture button below to record your time spent reading and your answers to the following learning reflection questions, which align with Te Whanake reflection requirements (answer three or more):

- What were the key learnings from this activity?

- How does what you learnt benefit you, or why do you appreciate the learning?

- If you apply your learning, what are the benefits or implications for others?

- Think of a situation where you could apply this learning. What would you do differently now?

- If an opportunity to apply this learning comes up in the future, what measures can be taken to ensure the learning is applied?

- Can you think of any different ways you could apply this learning?

- Are there any skills you need to develop to apply this learning effectively?

1. Te Whatu Ora. Priority Childhood Immunisation Policy Statement. Aotearoa New Zealand National Immunisation Programme, version 1.0. December 2022.

2. Sheth JN, Frazier GL. A model of strategy mix choice for planned social change. Journal of Marketing 1982;46(1):15–26.

![New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa editor Barbara Fountain, RNZCGP president elect and Tauranga-based specialist GP Luke Bradford, Ministry of Health clinical chief advisor rural health Helen MacGregor, and Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora clinical director primary and community care Sarah Clarke [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/1.%20Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20Luke%20Bradford%2C%20Helen%20MacGregor%20and%20Sarah%20Clarke.jpg?itok=091NETXI)

![Ngāti Porou Oranga specialist GP Elina Pekansaari and Te Nikau Hospital specialist in general practice and rural hospital medicine David Short [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/2.%20Elina%20Pekansaari%20and%20David%20Short.jpg?itok=h5XfSBVM)

![Locum specialist GP Margriet Dijkstra and OmniHealth regional operations manager (southern) Patricia Morais-Ross [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/3.%20Margriet%20Dijkstra%20and%20Patricia%20Morais-Ross.jpg?itok=jkrtRfJC)

![Golden Bay dairy farmer and dairy industry health and safety doctoral student Deborah Rhodes, and Golden Bay Community Health specialist GP Rachael Cowie [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/4.%20Deborah%20Rhodes%20and%20Rachael%20Cowie.jpg?itok=oM0_GcJc)

![Hauora Taiwhenua clinical director rural health Jeremy Webber, Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine president Rod Martin and Observa Care director of business operations Deborah Martin, the wife of Dr Martin [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/5.%20Jeremy%20Webber%2C%20Rod%20Martin%20and%20Deborah%20Martin%2C%20the%20wife%20of%20Dr%20Martin.jpg?itok=P_aGmX_H)

![Spark Health chief executive John Macaskill-Smith and client director Bryan Bunz [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/6.%20John%20Macaskill-Smith%20and%20Bryan%20Bunz.jpg?itok=5yJvVZ0I)

![Associate dean (rural) Kyle Eggleton, third-year medical student Roselle Winter, and second-year pharmacy student Alina Khanal, all from the University of Auckland [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/7.%20Kyle%20Eggleton%2C%20Roselle%20Winter%20and%20Alina%20Khanal.jpg?itok=RQLd3TEs)

![Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora clinical editor and specialist in general practice and rural hospital medicine Anu Shinnamon, and Whakarongorau chief clinical officer Ruth Large [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/8.%20Anu%20Shinnamon%20and%20Ruth%20Large.jpg?itok=i5TMswY9)

![Te Kahu Hauora Practice specialist GP Jane Laver and Ngāti Kahungunu ki Tāmaki-nui-a-Rua chief operations manager Tania Chamberlain [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/9.%20Jane%20Laver%20and%20Tania%20Chamberlain.jpg?itok=jtMklaCZ)