For older people and frail people, the long-term benefit of medicines reduces and the potential for harm from adverse effects increases. When the benefit–risk balance changes in this way, medicine review and optimisation are important to simplify the therapeutic regimen, reduce inappropriate medicines and minimise risks. In this article, pharmacist prescriber Linda Bryant uses two case studies to illustrate important considerations during medicine reviews

HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer

HPV-related oropharyngeal cancer

We're republishing this article in our Undoctored free access space so it can be read and shared more widely. Please think about supporting us and our journalism – subscribe here

World Head and Neck Cancer Day on 27 July is an opportunity to remind all healthcare providers to take part in education, early diagnosis and prevention of human papillomavirus-related oropharyngeal cancer

Ramesh Pandey and Swee Tan

This article has been endorsed by the RNZCGP and has been approved for up to 0.25 CME credits for the General Practice Educational Programme and continuing professional development purposes (1 credit per learning hour). To claim your credits, log in to your RNZCGP dashboard to record this activity in the CME component of your CPD programme.

Nurses may also find that reading this article and reflecting on their learning can count as a professional development activity with the Nursing Council of New Zealand (up to 0.25 PD hours).

Prevalence – there are approximately 315 HPV-positive and 53 HPV-negative new OPC cases per year in New Zealand.

Incidence – increases with age, more rapidly after age 50, and peaks between ages 60 and 70.

Gender – affects men four times more than women.

Risk factors – HPV infection has overtaken smoking and alcohol consumption as the main risk factor for OPC.

Common symptoms – persistent (longer than three weeks) throat pain, otalgia, difficulty swallowing and neck swelling.

Work-up – head and neck examination, including nasendoscopy by an otolaryngologist – initial investigation with fine needle biopsy of the neck lump, biopsy of the primary site, and staging scans (usually a PET-CT and an MRI scan of the head and neck).

Treatment – usually six to seven weeks (30–35 fractions) of radiotherapy with concurrent platinum-based chemotherapy or cetuximab. Early-stage disease can be treated with surgery alone plus possible adjuvant radiotherapy with or without chemotherapy over six weeks (30 fractions).

Prognosis – five-year overall survival is 80 per cent for HPV-positive and 40 per cent for HPVnegative tumours.

Sequelae of treatment – loss of taste and saliva production, tinnitus, hearing loss, dizziness, neuropathy, chronic fatigue, trouble swallowing, neck stiffness and pain, and loss of dentition.

Prevention – remind all patients aged nine to 26 years to undergo free HPV vaccination.

Sitting in our boardroom at our multidisciplinary head and neck cancer meeting, attended by over 10 dedicated clinicians, with other members across different DHBs attending via video conferencing, we were poised to discuss a 53-year-old male non-smoker with a four-month history of throat discomfort, otalgia and a large neck mass.

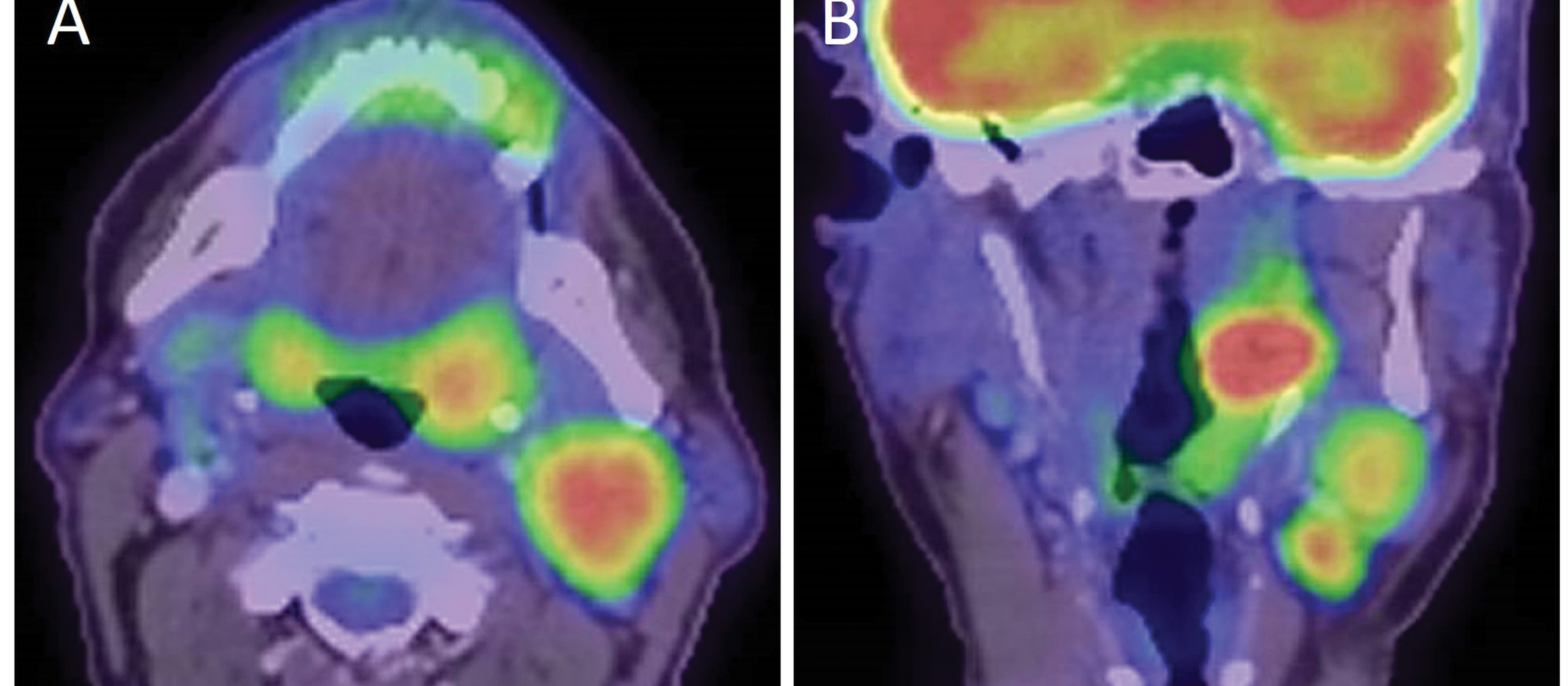

A video of the nasendoscopy shows a 3cm left-sided tonsillar mass, and we review an MRI scan of the head and neck, and positron emission tomography CT (PET-CT) of the body. There are several metastases affecting lymph nodes in the neck (Figure 1) but, thankfully, no distant metastases.

Biopsies show human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive squamous cell carcinoma. The panel agrees that the best treatment option is radiotherapy with concurrent chemotherapy with a curative intent.

The team dentist will review and extract any unhealthy teeth within the radiotherapy fields, and a dietitian and a speech-language therapist will be engaged to assist recovery and rehabilitation.

Oropharyngeal cancer (OPC) is potentially curable, but the sequelae of achieving cure are life changing due to the morbidity that treatment entails. Patients end up with loss of taste and saliva production, tinnitus, hearing loss, dizziness, neuropathy, chronic fatigue, trouble swallowing, neck stiffness and pain, and loss of dentition.

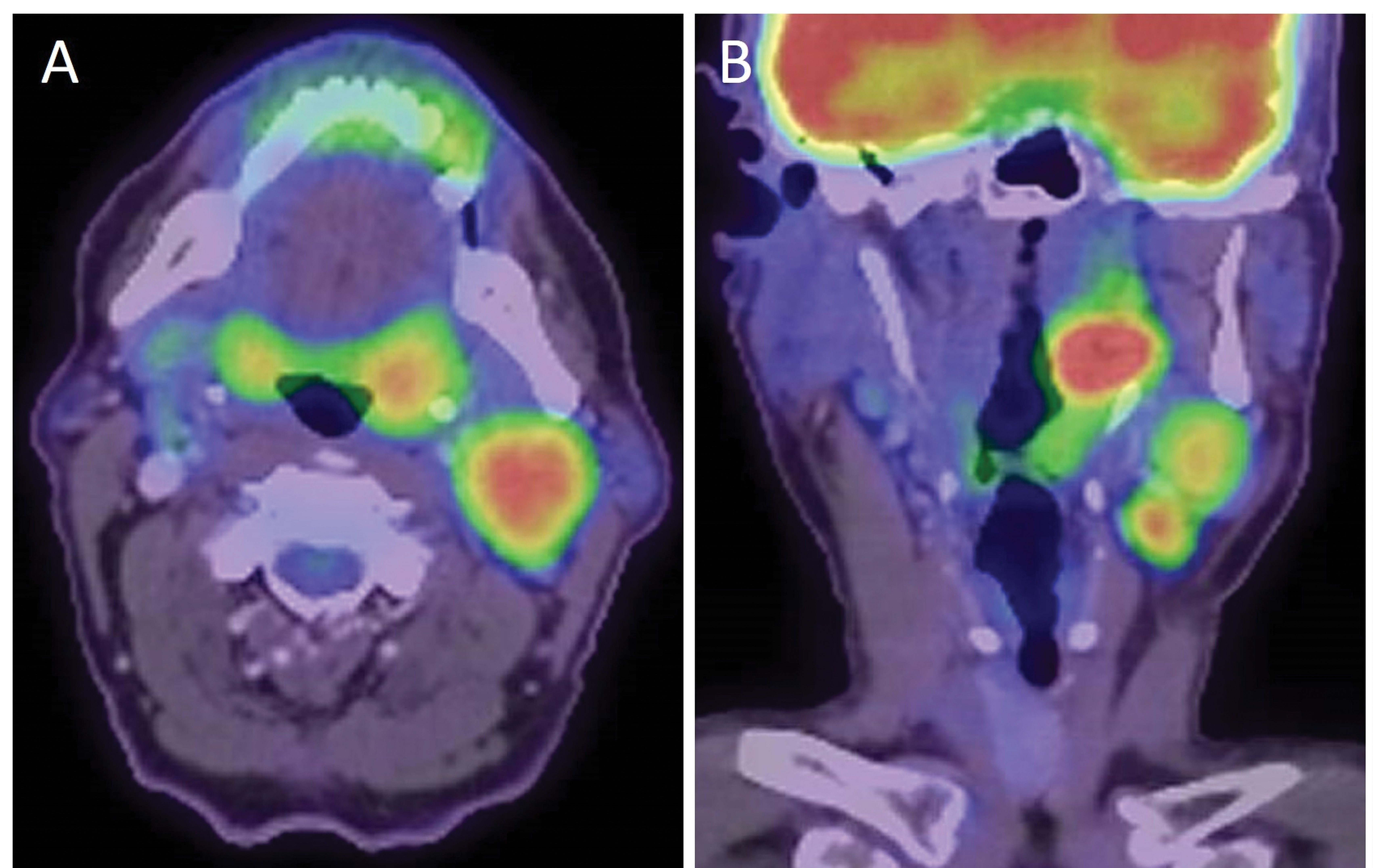

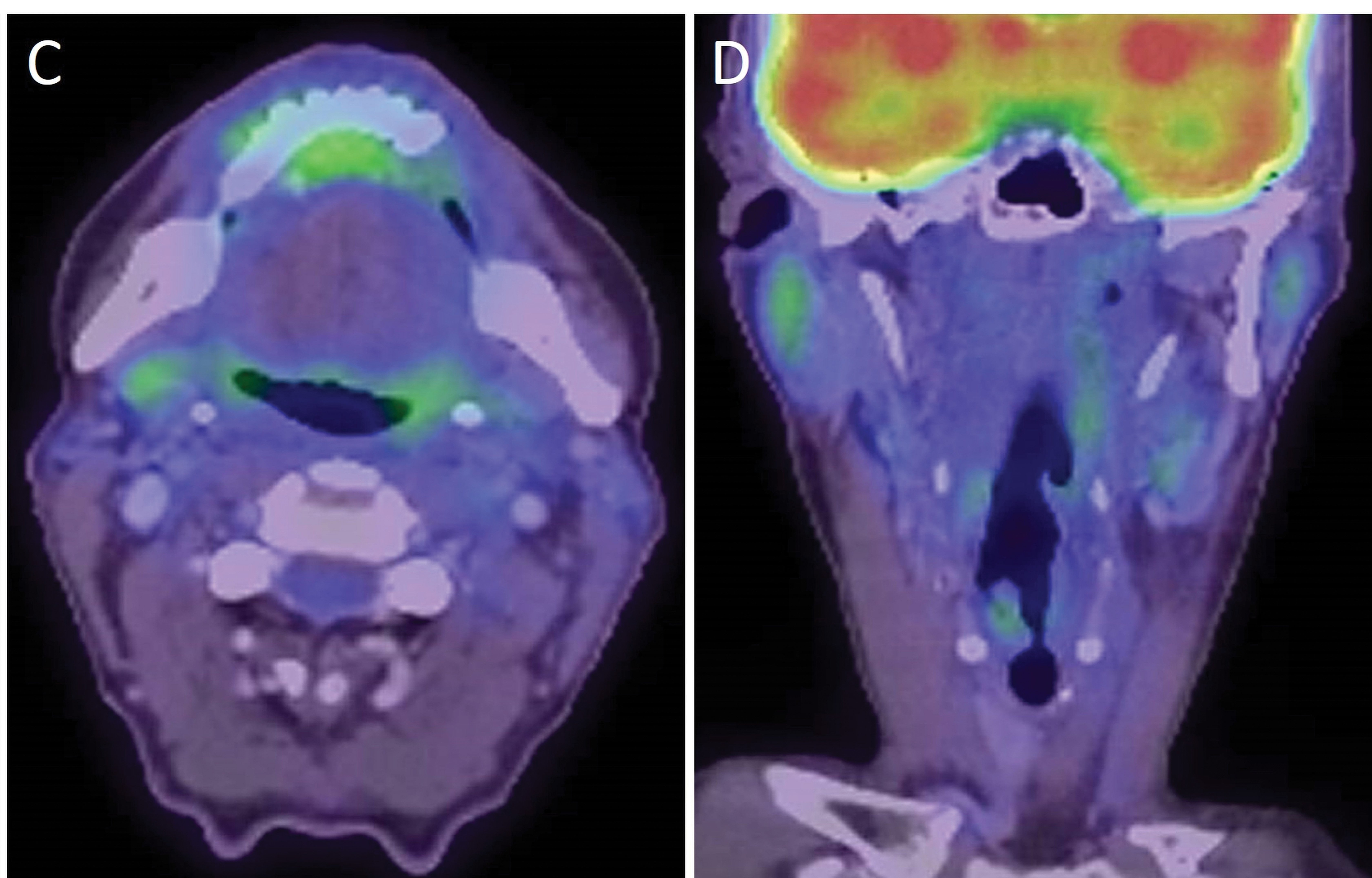

Seeing patients return to their normal lives after cancer is fulfilling, but they pay a price to attain this, and survivors deal with ongoing issues that can affect them emotionally. The ability to intervene and change the natural history of this patient’s condition is rewarding (Figure 2), but is there a better way?

We are treating increasingly more patients with head and neck cancer. The incidence of OPC has been rising in New Zealand since 2005,1 and a retrospective review over a 20-year period to 2010 shows almost fourfold greater incidence in men (1.87 per 100,000) than in women (0.47 per 100,000).2

Over the last several years, the traditional risk factors for head and neck cancers, such as smoking and alcohol consumption, have been replaced by HPV infection for OPC. Our study investigating the changing prevalence of HPV-positive OPC in patients residing in the greater Wellington region demonstrates a tripling of the proportion of HPV-positive OPC over the 20-year period.3

Patients with HPV-positive OPC are 10 years younger than those with HPV-negative OPC, and they are less likely to have smoked.3 The study confirms the increased prevalence of HPV-positive OPC in New Zealand and demonstrates its disproportionate burden on men, which is in keeping with other developed nations, such as Australia,4 the US5 and Sweden.6

In 2018, there were an estimated 95 new OPC cases and 25 OPC-related deaths in New Zealand.7 However, a recent national survey shows there were 315 HPV-positive and 53 HPV-negative new OPC cases in 2020 (unpublished data). This compares with the approximately 190 women diagnosed with cervical cancer and 72 related deaths each year.

The oropharyngeal region, which includes the tonsils, base of tongue, soft palate and pharyngeal walls, is the most studied in terms of causality with HPV.8,9

HPV can be transmitted by skin-to-skin contact or oral sex. Although the rate of HPV infection is high, most people infected do not develop cancer. For the majority, HPV infection is transient and becomes undetectable within one year, although it may remain latent and become reactivated many years later. Recurrent HPV infection can also occur.10

There are more than 150 distinct subtypes of HPV, which are grouped according to their oncogenic capacity as high risk and low risk, with some low-risk subtypes found to cause benign conditions, such as genital warts. High-risk HPV subtypes, such as HPV16 and HPV18, play a significant role in lower genital tract pre-cancers and cancers: cervical (almost 100 per cent), vaginal (~90 per cent), anal (~80 per cent), penile (~50 per cent) and vulval (~40 per cent); plus oropharyngeal (~75 per cent).11

It is unclear why the oropharynx is more susceptible to HPV-induced cancer than other head and neck sites. One reason may be that the oropharynx, cervix and anogenital regions offer easy access for infection. The tonsils, which contain deep invaginations of the mucosa, may facilitate viral access to basal cells.

HPV is a double-stranded circular DNA virus. Viral integration into the host genome at random sites is important for malignant transformation. This linearises the HPV genome, interrupting the viral DNA within the E1/E2 open reading frame, resulting in a loss of the E2 viral repressor and overexpression of E6 and E7 oncogenes.12

The E6 protein degrades p53, the Guardian of the Genome, resulting in activation of telomerase reverse transcriptase and immortalisation of cells. The E7 protein binds to retinoblastoma protein – a tumour suppressor protein – removing its antitumour mechanism. The E7 protein also possibly activates cyclins E and A, which are involved in the cell cycle.12

The result of HPV infection with high-risk HPV subtypes is oncogenic proteins that disrupt inherent antitumour protective mechanisms, allowing a fertile bed for malignancy to develop, especially in concert with environmental factors.12

A 2017 New Zealand study found that just under 80 per cent of OPC cases identified from the cancer registry were attributable to HPV, 98 per cent of which are due to HPV16.13

The nonavalent HPV vaccine Gardasil is approved in New Zealand for use in females aged nine to 45 years, and in males aged nine to 26 years. It is given as a two-dose schedule in individuals aged 14 and under, and as a three-dose schedule in older individuals and immunocompromised individuals from age nine.10

Without vaccination, approximately 80 per cent of sexually active adults will be infected by at least one strain of HPV during their lives.

While the recommendation for vaccination has not been specifically targeted towards OPC, it is the only reliable method to prevent OPC. Vaccination with Gardasil has potential to substantially reduce the rates of OPC and other cancers caused by HPV subtypes 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58.

It is important to note that vaccination does not negate the need for screening for cervical, vulvar, vaginal, anal, oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers.14

Since 1 January 2017, HPV immunisation has been free in New Zealand for both males and females aged nine to 26. However, vaccination rates are too low and have yet to reach the target of 75 per cent coverage across all DHBs, which the Ministry of Health aimed to achieve by December 2017.

It appears that a significant cohort may have missed out on the vaccine through the school-based programme and are unaware that it is available to them or may only be partially vaccinated. Data from the vaccine provider Seqirus/MSD show that 20,000 fewer doses were administered in 2020 compared with the previous year, which indicates approximately 10,000 children and young people missed out on being vaccinated.

The success of a national HPV vaccination programme is dependent on an effective vaccine achieving high coverage to reduce transmission of HPV infections. New Zealand’s HPV vaccine coverage rate is currently 68 per cent (in females)7 and increasing; however, it needs to be better. In 2017, Australia had a coverage rate of 80.2 per cent for females and 75.9 per cent for males for three doses.15 According to recent modelling studies, it has been suggested that vaccination rates may need to be at least 80 per cent to achieve herd immunity.7

Therefore, it is vital that parents and young people (ie, those up to their 27th birthday) are aware of the benefits provided by the vaccine and of the subsidised HPV vaccination programme.

A positive recommendation by a trusted healthcare professional has been shown to strongly influence the likelihood of vaccine uptake. To this end, healthcare providers have a responsibility to ensure their knowledge around HPV vaccines is up to date.

Patients with HPV-positive OPC are highly curative if referred early. The presence of HPV is positively prognostic compared with HPV-negative tumours, although the morbidity of treatment is significant and prevention with vaccination must be encouraged.

The Head and Neck Cancer Foundation Aotearoa and the Sexually Transmitted Infections Education Foundation are committed to promoting vaccine uptake to parents and young people and are working with the ministry to develop and support strategies to enable healthcare professionals to confidently recommend and encourage access to the HPV vaccine.

Head and Neck Cancer Foundation Aotearoa ‒ headandneckcancer.org.nz

Sexually Transmitted Infections Education Foundation ‒ stief.org.nz

New Zealand HPV Project ‒ hpv.org.nz

Head and Neck Cancer Support Network ‒ headandneck.org.nz

Ramesh Pandey is a radiation oncologist and the chair of the Head and Neck Tumour Stream at MidCentral DHB Regional Cancer Treatment Service; Swee Tan is a head and neck cancer surgeon at Hutt Valley DHB, chair of Head and Neck Cancer Foundation Aotearoa, and executive director of Gillies McIndoe Research Institute

You can use the Capture button below to record your time spent reading and your answers to the following learning reflection questions:

- Why did you choose this activity (how does it relate to your PDP learning goals)?

- What did you learn?

- How will you implement the new learning into your daily practice?

- Does this learning lead to any further activities that you could undertake (audit activities, peer discussions, etc)?

- Elwood JM, Youlden DR, Chelimo C, et al. Comparison of oropharyngeal and oral cavity squamous cell cancer incidence and trends in New Zealand and Queensland, Australia. Cancer Epidemiol 2014:38:16–21.

- Chelimo C, Elwood JM. Sociodemographic differences in the incidence of oropharyngeal and oral cavity squamous cell cancers in New Zealand. ANZ J Public Health 2015;39(2):162–67.

- Kwon HJ, Brasch HD, Benison S, et al. Changing prevalence and treatment outcomes of patients with p16 human papillomavirus related oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in New Zealand. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2016;54(8):898–903.

- Hong AM, Grulich AE, Jones D, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx in Australian males induced by human papillomavirus vaccine targets. Vaccine 2010;28:3269–72.

- Chaturvedi AK, Engels EA, Pfeiffer RM, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) and rising oropharyngeal cancer incidence in the United States. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4294–301 .

- Näsman A, Attner P, Hammarstedt L, et al. Incidence of human papillomavirus (HPV) positive tonsillar carcinoma in Stockholm, Sweden: an epidemic of viral-induced carcinoma? Int J Cancer 2009:125:362–66.

- Petousis-Harris H, Alley L. Human Papillomavirus Vaccination: Hesitancy and Uptake. Research Review; 2019. https://bit.ly/3x8i6V3

- Gillison ML, Koch WM, Capone RB, et al. Evidence for a causal association between human papillomavirus and a subset of head and neck cancers. Natl Cancer Inst 2000;92:709–20.

- Stransky N, Egloff AM, Tward AD, et al. The mutational landscape of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Science 2011;333(6046):1157–60.

- Ministry of Health. Immunisation Handbook 2020: Human papillomavirus. https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/immunisation-handbook-2020/10-human-papillomavirus

- Professional Advisory Board of the Sexually Transmitted Infections Education Foundation. Guidelines for the Management of Genital, Anal and Throat HPV Infection in New Zealand, 9th edition. Auckland, NZ: Sexually Transmitted Infections Education Foundation; 2017. https://bit.ly/3qAWzlp

- Kumar V, Abbas A, Aster J. Neoplasia. Robbins and Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease, 9th edition (pp. 326-27). Elsevier; 2015.

- Lucas-Roxburgh R, Benschop J, Lockett B, et al. The prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal cancer in a New Zealand population. PLoS ONE 2017;12(10):e0186424.

- Merck. FDA Approves Merck’s GARDASIL 9 for the Prevention of Certain HPV-Related Head and Neck Cancers. 12 June 2020. https://bit.ly/3AqyrXc

- Australian Government Department of Health. www.health.gov.au

![New Zealand Doctor Rata Aotearoa editor Barbara Fountain, RNZCGP president elect and Tauranga-based specialist GP Luke Bradford, Ministry of Health clinical chief advisor rural health Helen MacGregor, and Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora clinical director primary and community care Sarah Clarke [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/1.%20Barbara%20Fountain%2C%20Luke%20Bradford%2C%20Helen%20MacGregor%20and%20Sarah%20Clarke.jpg?itok=091NETXI)

![Ngāti Porou Oranga specialist GP Elina Pekansaari and Te Nikau Hospital specialist in general practice and rural hospital medicine David Short [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/2.%20Elina%20Pekansaari%20and%20David%20Short.jpg?itok=h5XfSBVM)

![Locum specialist GP Margriet Dijkstra and OmniHealth regional operations manager (southern) Patricia Morais-Ross [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/3.%20Margriet%20Dijkstra%20and%20Patricia%20Morais-Ross.jpg?itok=jkrtRfJC)

![Golden Bay dairy farmer and dairy industry health and safety doctoral student Deborah Rhodes, and Golden Bay Community Health specialist GP Rachael Cowie [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/4.%20Deborah%20Rhodes%20and%20Rachael%20Cowie.jpg?itok=oM0_GcJc)

![Hauora Taiwhenua clinical director rural health Jeremy Webber, Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine president Rod Martin and Observa Care director of business operations Deborah Martin, the wife of Dr Martin [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/5.%20Jeremy%20Webber%2C%20Rod%20Martin%20and%20Deborah%20Martin%2C%20the%20wife%20of%20Dr%20Martin.jpg?itok=P_aGmX_H)

![Spark Health chief executive John Macaskill-Smith and client director Bryan Bunz [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/6.%20John%20Macaskill-Smith%20and%20Bryan%20Bunz.jpg?itok=5yJvVZ0I)

![Associate dean (rural) Kyle Eggleton, third-year medical student Roselle Winter, and second-year pharmacy student Alina Khanal, all from the University of Auckland [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/7.%20Kyle%20Eggleton%2C%20Roselle%20Winter%20and%20Alina%20Khanal.jpg?itok=RQLd3TEs)

![Health New Zealand Te Whatu Ora clinical editor and specialist in general practice and rural hospital medicine Anu Shinnamon, and Whakarongorau chief clinical officer Ruth Large [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/8.%20Anu%20Shinnamon%20and%20Ruth%20Large.jpg?itok=i5TMswY9)

![Te Kahu Hauora Practice specialist GP Jane Laver and Ngāti Kahungunu ki Tāmaki-nui-a-Rua chief operations manager Tania Chamberlain [Image: NZD]](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_cropped_100/public/2025-05/9.%20Jane%20Laver%20and%20Tania%20Chamberlain.jpg?itok=jtMklaCZ)