For older people and frail people, the long-term benefit of medicines reduces and the potential for harm from adverse effects increases. When the benefit–risk balance changes in this way, medicine review and optimisation are important to simplify the therapeutic regimen, reduce inappropriate medicines and minimise risks. In this article, pharmacist prescriber Linda Bryant uses two case studies to illustrate important considerations during medicine reviews

Cumulative pandemic deaths: a graph more effective than 1,000 words

Cumulative pandemic deaths: a graph more effective than 1,000 words

Ian Powell is a former executive director of the Association of Salaried Medical Specialists. He is now a health commentator based on the Kapiti Coast. This opinion piece has been republished from his blog Otaihanga Second Opinion

A good graphic illustration is well-known to convey a much stronger message than words. For a long time this was emphasised by the saying one picture is worth a thousand words. It was popularised with great success by an American advertising executive, Fred R. Barnard, in the 1920s.

Barnard gave it an Asian origin to give it more credibility but he didn’t need to. It became a self-evident truth. The same can be said for a graph, another form of illustration.

Usually this requires some simplicity to the graph but, if done well, even a busy graph can also beat 1,000 words for effectiveness of message.

Dimitry Kobak is a Russian research scientist and a group leader based at Tübingen University, Germany. Among his activities is a repository on cumulative deaths under the Covid-19 pandemic which he owns. His calculations are extrapolated from World Health Organisation data.

I first came across Kobak’s work via Twitter in a retweet (10 February) from Dr Carl Horsley, an intensive care specialist and senior clinical leader at Middlemore Hospital. His retweet was a remarkable busy but telling graph from Kobak’s repository.

In his retweet Horsley added the following words: “Just a reminder because it’s so easy to take it for granted or forget.” These 14 words say so much. Maybe not as much as in Shakespeare’s 14 sonnets but still quite a lot.

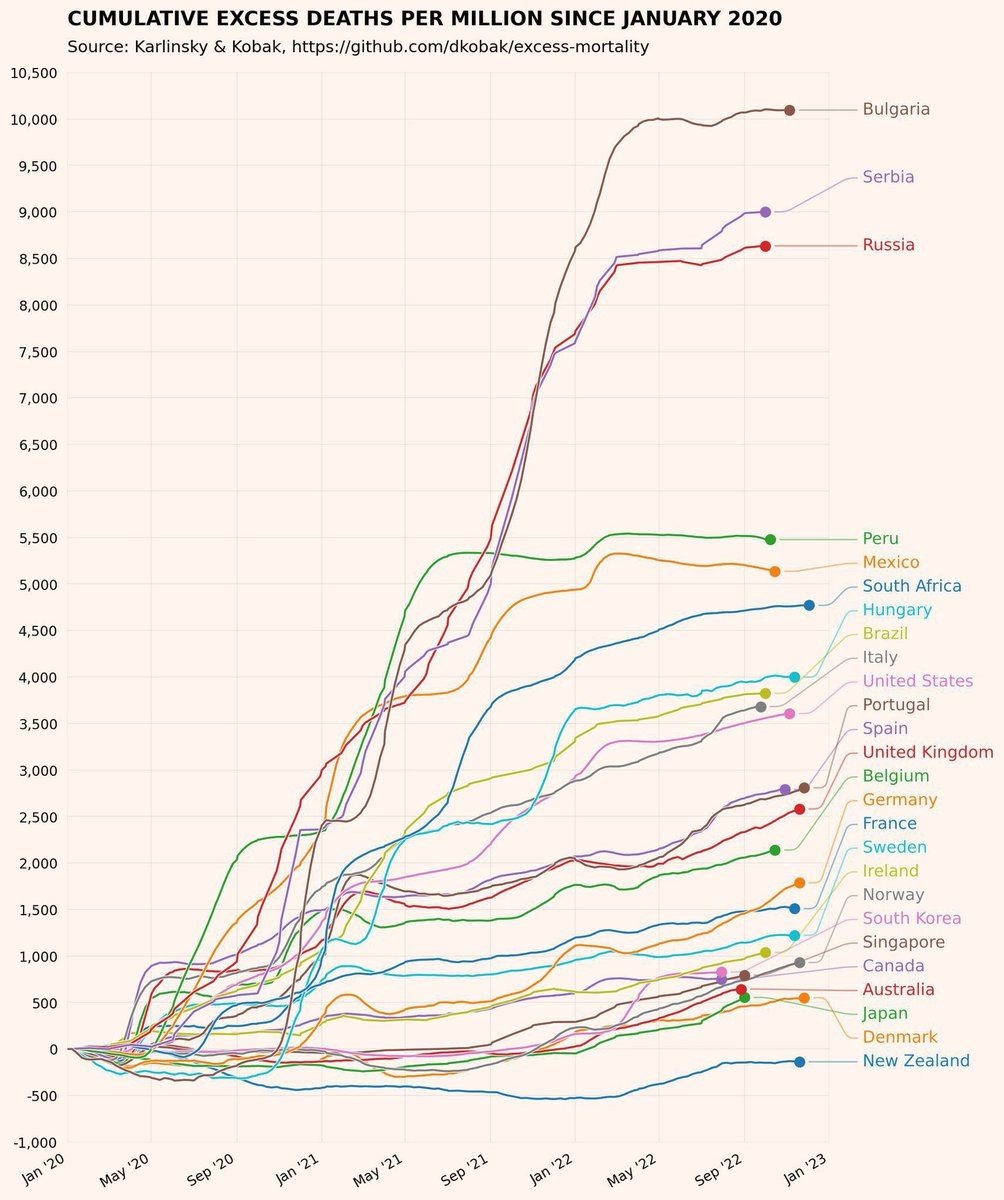

The graph covers the three-year period from January 2020, when the pandemic commenced, to January 2023. This includes the impact of the Omicron variant which saw a dramatic increase in mortality from late 2021 although not reaching Aotearoa New Zealand until early the following year.

These are not just Covid-19 death rates. They are a comparison of excess total cumulative deaths million. But, because the starting point is the commencement of the pandemic, it is arguably the most scientific way, to date at least, of measuring the impact of Covid-19 on mortality.

So what does this graph tell us?

The graph compares 23 largely economically developed countries. The three worst performing countries (ie, highest excess cumulated death rate per million) were Bulgaria (10,500 cumulative deaths per million), Serbia (nearly 9,500) and Russia (over 8,500).

Below are some of the other countries spread between the worst (and followed by the best three):

- Italy over 4,000

- United States over 4,000

- Portugal over 3,500

- United Kingdom over 3,000

- Germany over 2,500

- France nearly 2,500

- Sweden over 2,000

- Ireland nearly 2,000

- Norway over 1,500

- Singapore over 1,000

- Canada nearly 1,000

- Australia nearly 1,000

Australia achieved the fourth lowest excess mortality rate. And then there are the top three of the 23 countries. Third is Japan (nearly 500) while second is Denmark (around 250). Who is first? New Zealand!

But what is more remarkable than this outstanding result is that of the 23 countries, New Zealand is the only one not to have an excess of death rate at all (under 0 to be precise).

How did this happen? Overwhelmingly it is due to the success of Aotearoa’s public health measures which were based on an elimination, rather than mitigation, of community transmission strategy. This included the lockdowns and strong border restrictions.

What distinguished us from most of the rest of the world was not just the elimination choice. It was the speed in which the Labour-led government implemented it. New Zealand was also advantaged from its distance from the early coronavirus spread from China to Europe. Geographic location gave us an advantage but that was not enough on its own. Good decision-making and implementation were the most decisive factors

The outcome was New Zealand being a world leader in the Covid-19 response for 2020 and much of 2021. This included economic performance because our lockdowns were so effective we had less of them than almost all other countries.

A not always understood consequence of this transmission elimination strategy was that it also impacted on influenza mortality. During this period flu mortality rates plummeted. Movement (and proximity) among New Zealanders and tourism are big flu drivers. Halting tourism and reducing proximity of people means reducing flu.

Much of New Zealand’s success was pre-vaccine. Contrary to a prevalent but inaccurate narrative promoted by some, New Zealand’s vaccine rollout was also world leading.

Full vaccination coverage was higher than most developed economies, including the European Union (which negotiated as a bloc), United Kingdom and United States. This was despite being a smaller economy and a long way away from vaccine manufacturing countries.

The vaccination rollout owed much to having a district health board (DHB) system in which local statutory authorities were required to know and understand the health statuses of their geographically defined populations, along with community and other health providers.

DHBs were unfairly scapegoated by some, including Associate Health Minister Peeni Henare, for problems (communication and local implementation) in rollout progress. But this was because they were under excessive micro-management control by the Ministry of Health which constrained their communications and how they rolled their vaccines out.

After a struggle DHBs were able to push back and, working with community bodies, accelerate the rollout. This helped reinforce New Zealand’s successful achievement of a remarkably low mortality rate. The irony of the government decision to abolish DHBs should not be lost on anyone.

Since October 2021 I have been increasingly disappointed with the government’s pandemic response. It has drifted towards laissez-faire as it sought to distance itself from responsibility.

Rather than a world leader we dropped to somewhere in the middle of the pack. And then Omicron came which made an elimination strategy ineffective because of its speed of transmission.

The pandemic is still with us with little sign of light at the end of the tunnel. The most recent update (10 February) reports 32 deaths over the preceding week: 8396 new cases, 171 in hospital and 32 deaths. That’s more Covid deaths in one week than in all of 2020 and 2020 along with non-stop greater pressure on public hospitals.

The shift to a more laissez-faire response and the impact of Omicron make the astute observation of Dr Carl Horsley even more pertinent.

If, back in early 2020, the government had followed the mitigation of community transmission strategy, then Aotearoa would at best have been in the middle of Dimitry Kobak’s 23 country comparison of excess deaths. Not to the same extent but we would have fared much worse had the government not implemented the elimination strategy and closed the borders as quickly as it did. It meant that compared to most countries we were not playing catch-up.

New Zealanders owe so much to Professor Michael Baker and his colleagues for providing the right expert advice to government. Wisely they looked to the progress of the elimination strategy adopted in parts of Asia comparing it with the disastrous effects of mitigation in Europe. This gave them a much better understanding of the unique nature of this virus.

I have several criticisms of the leadership of former Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern from October 2017 to January 2023. But there is no doubt in my mind that New Zealanders also owe so much to her leadership in both accepting this expert advice and the effectiveness of its implementation.

As Dr Horsley says, we need to be reminded that it is easy to take for granted or forget the extraordinary success of the elimination of community transmission strategy.